In this article, you will learn what Static Analysis is, why it is loved and hated by developers at the same time, and how it can be used for writing better software or to annoy your colleagues.

Imagine you have a tiny detective constantly inspecting your code, searching for hidden mistakes before they cause real trouble. That’s what Static Analysis does. This method/tool automatically finds bugs, code smells and inconsistencies. Sometimes in a matter of seconds, and without missing a beat.

If you haven’t seen this before, it may sound like magic. On the other hand, if you have seen it before, you know that it can be annoying, too. Regardless of where you are right now, this article – and hopefully this blog as a whole – should be useful.

One important note: Static Analysis also exists for models, for requirements, and even for Sudoku. We will come to that later. Let’s start with code.

Humans make many mistakes

A good developer anticipates errors and writes clean, robust code. A great one knows that we all could use that little detective. Humans naturally make mistakes due to fatigue, time pressure, or ignorance. Even the world’s best software teams are no different.

Moreover, many studies have demonstrated that humans are also poor at detecting errors when asked to do so. I am not talking about the tired feeling on Monday morning, before your coffee. No – human brains simply lack the cognitive capacity to consider each and every corner case. For instance, in code inspections, even when conducted by teams of three to eight individuals, reviewers typically identify only about 60% to 75% of errors in a software module. Other numbers suggest that approximately 1% of all lines of code may still contain errors after reviews.

How can we help humans make fewer mistakes? The Jeopardy answer is …

What is Static Analysis?

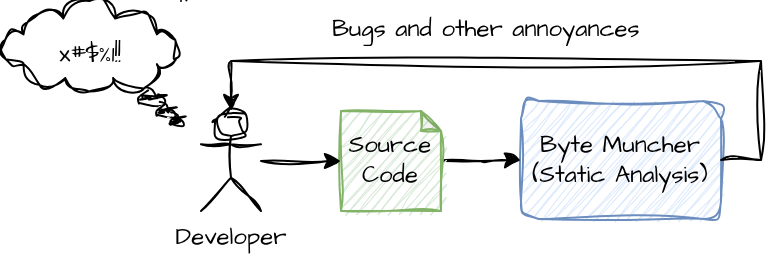

Unlike traditional testing methods that require running the program (some call it ”dynamic analysis”) with specific inputs, Static Analysis just “reads” your code. It consumes source code, byte code, or even compiled binaries, and analyzes them systematically to find bugs. It tries to consider all possible inputs, and all corner cases. Like humans, but without getting tired or having a bias. So, in principle: Code in – bugs out. There are various methods to achieve that, but let’s keep that for another day.

Typical warnings are about memory access errors, numeric overflows, missing variable initialization and style violations, but also more abstract things like SQL injection risks, performance bottlenecks and data leaks.

This is, of course, very useful:

- It catches bugs early (before they hit testing & production), saving time and money.

- It helps with code consistency (enforcing style guides) and helps me write better code.

- It finds security vulnerabilities before attackers do.

It sounds very good. And hence, not surprisingly, Static Analysis is highly recommended by many industrial safety and security standards. Your car, your airplane, likely even your operating system, they all have been created with the help of Static Analysis, to increase the chances that they work reliably under all possible conditions.

Static Analysis and I had a slow start

When I discovered Static Analysis in my mid-twenties, I was skeptical and saw it almost as cheating. Maybe I was too proud to admit I could use help, but I also wanted to write perfect code. Hence, Static Code Analysis and I had somewhat of a game:

- I wrote my code,

- I looked at it thoroughly to find and fix bugs,

- I made some more changes to make sure the tool wouldn’t get me,

- Finally, I run a Static Code Analysis to get confirmation that I am a great developer.

Guess what – I wasn’t. More often than not, the tool still found something. Even worse than a broken ego, I have wasted a lot of time like that.

My motto was: “real developers use emacs, and fight bugs with their bare hands”

Once I started to accept that even experienced developers make mistakes, and that there is a blindness towards your own code (have you ever tried proofreading your own texts?), it started to be useful. Since then, I have written a lot of critical software (e.g., flight controllers and communication stacks), and I use Static Analysis as often as possible. It finds all the stupid mistakes, and allows me to concentrate on the software design. Today, I am almost angry if have to write code without it, especially when there is no compiler that can help at least a little bit (yes Python, you).

The Many Caveats of Static Analysis

With Static Analysis, we should be in a world without bugs, where software works reliably and nobody ever has to do any overtime to fix bugs. And, since it finds all bugs, we could get rid of more annoying things like writing tests.

But as we know, this is not the world we are living in. Software still has sufficient bugs, so what’s wrong? There are several reasons why Static Analysis struggles to make this world a fairy tale:

- It can miss bugs (”False Negatives”): Unlike humans, Static Analysis doesn’t have cognitive limitations, but it has computational ones. It is notoriously difficult to write a tool doesn’t miss anything. Although some methods can achieve this (to be discussed in a future post), it is very rare, and it has a price. So if somebody claims their tool can find all bugs, be very skeptical. Empirical studies claim that the bug detection rate in the real world is somewhere between 20% and 90%.

- It can produce false warnings (”False Positives”): It may misunderstand your code, or it may just not be able to analyze it precisely enough. That is something which Static Analysis veterans probably know very well. This unfortunate property can become very annoying if the developer feels that most warnings are superfluous, sometimes also called “noise”.

- It doesn’t understand the meaning: Even if we had the perfect tool (which cannot exist), it could only check what is in the code. And the code itself does not say what it is supposed to do. For example, you could write a perfect Bubblesort algorithm, but it would be totally wrong if you use this as a flight controller. In other words, Static Analysis is mostly (not always, perhaps a topic for another future post) limited to finding only certain types of bugs like program crashes or bad coding style. But it cannot tell if your code makes any sense.

- It may take a long time to produce results: Depending on how you use it, it may require many hours or days to analyze your software. Personally, I don’t think this is a problem because – would a human be better? But in practice, time is money, and humans are easily impatient.

- Developers know better: Since Static Analysis can make mistakes, and developers know it, the results are sometimes misunderstood, ignored, or never examined. Human factors and processes play a very important role, and this blog will frequently come back to this topic.

- It slows you down: Every move you make will be seen and commented by that little detective. And, as discussed, we will inevitably get more friction when writing software. A slowdown during the creative coding phase is therefore very common.

All of that taken together, it means that we still need manual code reviews and dynamic tests to check that our software behaves as intended, and yet we are still missing bugs. You may even be in a situation where Static Analysis gives you zero benefits, when it throws too many warnings. Real bugs then become the famous needle in a haystack. You probably stop using the tool altogether, because it just wastes your time.

So why use it, anyway?

If Static Analysis is so limited and annoying, why do people go through the effort of using it? Because when used right, it can help you avoid plenty of bugs, and make everything else more efficient. Especially your debugging time will go down, and your quality will go up.

But don’t expect miracles, it will not be easy to get started. Static Analysis might complain about a thousand things. It might bruise your ego. But once you get over it and work with the practical limitations (of humans and tools), there is nothing like that feeling of accomplishment when its runs out of complaints and gives you a green light. This technology can help you do your best work. To get there, you have to be willing to adapt and learn. I will do my very best to share a lot of practical tips with you.

The Pursuit of Unhappiness

Freely adapted from a great philosopher, here are some tips to make Static Analysis absolutely terrible and to annoy your colleagues effortlessly:

- Use it very late. Ideally one day before software release. You will get a lot of warnings, which you cannot address. Now you can blame the technology and don’t need to doubt your software quality.

- Do not automate. You can waste more time if you use it manually, and ignore any sort of source control system or CI pipelines.

- Expect that the tool understands your code. Don’t give any context. It would be cheating if you provide any architectural data, or trying to describe the context in which the software is used.

- Do not fix and compiler warnings. If you can compile like that, the tool has to handle it, too. Implementation-defined behavior is all the fun in software-engineering!

- Never touch the default settings. If the tool does not automatically know what you want, then it’s a bad tool.

On the other hand, if you are genuinely interested in eliminating bugs, and willing to adapt to the tool so that it can help you, I promise you will have benefits. With some effort, you will prevent severe issues way before your software is released. I have seen it many times, and I would be highly puzzled if that would not be possible for you.

So, here we are: If you are…

- An influencer: start talking about Static Analysis. We need you. As it turns out, only about half of open-source coding projects use Static Analysis (2016).

- A doer: just give it a try. Use it early while you are coding, when it is easy to react to warnings. Configure it in a way that helps you. I won’t recommend any tools here, but in case you really need some pointers, Google has your back.

- A manager: Ask yourself, how much benefit you would get if you could reduce bugs by only 10% (a very conservative number). If that would be net positive, enable your teams or fund a case study.

- Innovator: Static Analysis is a very exciting field. I have contributed myself, and there is always more work. How impactful would it be, if we could find an approach that is precise, fast, and sensitive at the same time?

Keep in mind, Static Analysis cannot vouch that your software is free from all kinds of bugs. But it can help you avoiding at least the stupid bugs, and that means you’ll save debugging time later.

What’s next?

In the next article, I will do my very best to explain how Static Analysis works.