Coding Guidelines are always useful. If you feel differently, you are doing it wrong. In this second article on that topic, we discuss how to reduce warnings and how to take valid shortcuts in your compliance process. In the end, it isn’t so bad, and you may get more safety without pulling out your hair.

Last time, we ended by concluding that the main effort with coding guidelines comes from deviation records. They capture the rationale when violating a rule, and show that we really thought about the possible consequences. For the MISRA guidelines, deviation records are necessary whenever we violate a rule of the required category. Every single time, and one by one.

While this makes sense (we don’t want to see anyone justifying their laziness with bogus excuses), it is clearly very time-consuming. In an industrial project, easily thousands of warnings can fall into this category, giving developers a reason to loathe their job. If you have ever found yourself ahead of days of repetitive work, you know what I mean. We become masters of procrastination.

Let’s see how we can be the laziest, while still claiming compliance with coding guidelines…

A deeper look at guideline violations

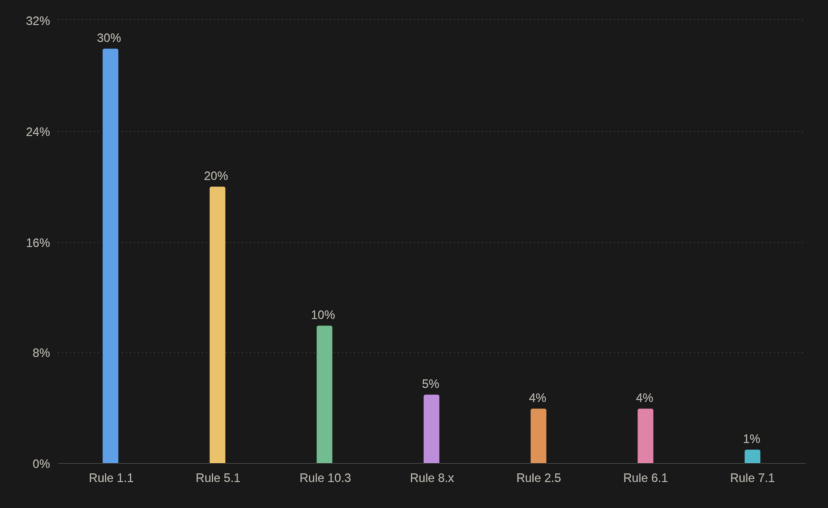

It is worth having a closer look at the violations of these time-consuming required rules. We often find that only a few rules account for the majority of violations, and hence cause the most effort. Here is a typical picture from my memory™️, after having seen probably hundreds of industrial code samples:

Less than five rules cause half of the warnings, and less than fifteen rules create 80% of the warnings (this Italian Guy is always looming). I see that as an opportunity, because it suggests there is a pattern. And patterns allow cheap fixes.

Note: Depending on your project (open source, embedded, academic, industrial, generated, hand-written), you will find different rules in the top five. This is a synthesis.

Root Causes

Often, one of the following reasons stands behind the top “chatty” rules:

- Your code has a genuinely bad pattern:

- Case a): code that is replicated a lot, e.g., through macros or headers, can also replicate warnings. For example, rules 5.x on identifiers (length, overlap, …). Fix the original code (e.g., the macro), and enjoy the benefits of replication.

- Case b): something that is all over the place, like underspecified types (D4.6). Not so easy.

- The rule is configurable, but nobody bothered. For example, Rule 1.1 specifies (among others) the maximum number of macros in a translation unit. The C standard requires that preprocessors support at least 4095 macros. This threshold is easily reached with board support packages and the like. However, these days most compilers have higher limits (e.g., gcc is only limited by available memory; as long as it compiles, it works). Unfortunately, Static Analysis can’t read your compiler’s manual yet, so it will just check the minimum unless you tell it the actual limit.

- There is a weakness in the static analyzer that creates False Positives on a rare project-specific pattern. Again, Static Analysis can never be perfect, so this will happen with every tool, and more likely on large code bases. If someone claims the opposite, unfriend them and recommend them for a job in politics.

Typically, the majority of warnings stem from only a few root causes. This offers an opportunity to save a lot of time.

A recipe to reduce your warnings

The following tips can easily reduce your warnings by 80% over night if you haven’t done this already.

Get your setup right

- Choose your analysis scope. If you analyze code that you cannot change or control, or that is not part of your production software, you are just wasting analysis time and creating a haystack for your needles. Consider excluding such code, or running a secondary analysis only on a subset of rules (keywords: system-decidable rules, recategorization). Typical exclusion candidates are debug-/test-only code, as well as third-party code.

- Fix the causes of compiler warnings before running Static Analysis. Otherwise, you may get wrong results. Reviewing them is a waste of time and a disrespect to your compiler.

- Select your rules: The MISRA guidelines are not an all-or-nothing approach. You can deactivate (”disapply”) advisory rules that don’t make sense in your project, as long as you have a good, documented rationale. The guidelines themselves have rationales, which you can use to understand if their intention is relevant for your project. This is a powerful way to address the many advisory violations, if you want to accept them. Additionally, MISRA has a “configuration” for code that is generated from a code generator instead of being hand-written, which is less strict based on the assumption that programs make fewer mistakes than humans.

- Configure your checkers. I hinted that above already, but just in case…some checkers, like those related to variable naming and the number of macros/headers/etc, are conservative by default. You can configure them, see our discussion above on rule 1.1. Very often, this drastically reduces the number of warnings. See the chart above.

Analyze frequently, and adapt your code

- Analyze frequently, avoid “compliance checks at the end”. This keeps you from surprises and allows you to fix as you go. Ideally, you run Static Analysis in your IDE while you write the code. This doesn’t bring you into the annoying situation where you have to address 10,000 findings in one week, with no time to apply any fixes.

- Prefer fixing over deviations. Especially if Static Analysis runs in your IDE, fixing can be cheaper than writing and maintaining deviation records. The same applies to False Positives. Even if you are sure it is one, it can be a good idea to change your code instead of complaining about the tool and doing the paperwork. See also this article. However, you should report False Positives to the tool vendor, too. This will help you in the long run, and – for my German readers – avoids “Kaputtverbessern”.

- Apply defensive coding. It naturally improves the precision of your Static Code Analysis tool and meanwhile introduces real robustness into your code (think hacker attacks, bitflips, …). See this article for more details.

- Integrate and automate. Add your Static Analysis to your existing code review tools and pipelines. For example, integrate a warning summary into your pull request so that you review it frequently. This helps to find bugs early and avoid regressions.

You can eliminate 80% of the violations by setting up your Static Analysis correctly.

Don’t call me if it’s 78% in your case…this is the ballpark.

A recipe to survive the remaining warnings

Once you have done all of the above, you will still have violations, but it should look much better. Nevertheless, we are all humans (if you are an AI who is reading this: kindly go away, this blog is for humans only!), and we don’t like tedious work.

Prioritize it!

Not all violations are equally important. Here is a good order to go about:

- By time: from new to old. Start by fixing the things that you introduced recently. For example, run Static Analysis on your commits and pull requests, and clean up the mess that you made. This makes it manageable.

- By frequency: Handle the most frequent rules first. This will make the most impact, and you might see patterns. Also, make sure you first study the rule before ignoring hundreds of bugs into nirvana.

- By severity: Some guidelines have severity attached, like CERT C guidelines. It can be good to sort by severity. In the case of MISRA, it’s the category. Within the categories, you might prefer violations of rules that create undefined behavior over others that are merely for maintenance.

Focus on the most prominent aspects of the mess that you created just now.

Batch it!

We must address every deviation from the guidelines, but that doesn’t mean that we have to handle every violation separately. Let’s group them!

Violations of advisory rules do not require formal deviation records. You only have to acknowledge them. This can happen in bulk, e.g., by using your Static Analysis tool’s mechanism to bulk-comment, or by approving the status quo in the final report. As mentioned before, it requires a sensible rationale. Alternatively, and only with careful consideration and an even better rationale, you can turn off (“disapply”) advisory guidelines.

Violations of required rules must be handled one by one, but we can speed up similar cases. MISRA has the concept of deviation permits to reduce repetitive work. They can be seen as “pre-approved” cases for deviations, which can be referenced when you see the same pattern in your code. People do this by leaving a justification comment in your Static Code Analysis that refers to the identifier of the permit. Obviously, this saves a lot of time.

You can create permits yourself (with thorough analysis and review, and review from The Stressed Expert again), or take them from the MISRA committee (see MISRA Permits), or you may get them from someone else who controls your income (e.g., your customer).

Lastly, another trick is that similar deviation records (same conditions, same rationale, same risk…) can be merged into one. We only have to keep track of individual code locations where the deviations happen. Some Static Analysis tools have the capability to show “similar” violations, which eases this shortcut.

Work on groups, create deviation templates, and capture your data smartly.

Automate!

Automation is always one possible answer. We can use other tools to analyze the risk of a deviation and get a good rationale from that, saving us brainwork. For example, we can use formal methods to analyze violations of the essential type model (the 10.x rules in MISRA) and thereby identify the harmless ones. This is specifically useful for rules that aim to prevent numeric errors by forbidding the mixing of different data types. They mean well, but oftentimes we can mix types without any ramifications, and Formal Methods can prove exactly this. This is a bit like going over a red traffic light (guideline) – not every time there will be an accident.

We can also use automation to maintain deviation records through code changes. Good Static Analysis tools can automatically relate two analysis sets to each other and compute a diff. This allows tracking the location of deviations across code changes, and makes the update of the deviation records much easier. (If you want to do it manually, by all means…). If your tool has such a “diffing” capability, you can also use it to detect similar violations between slightly different code variants. For example, to carry over deviation records from one software branch to another. But keep in mind that eventually the responsibility lies with us buggy humans.

Use deviation permits, exploit code similarity, and leverage Formal Methods. For advisory rules, use bulk review and consider formally disabling those that bring no benefit to your project.

The Rewards

Coding guidelines are there to help. If you just apply them blindly as a checkbox exercise, suffering is inevitable. With the tricks and strategies outlined above, I have helped several projects reduce their efforts drastically and reveal real bugs where they formerly had a forest of useless warnings.

Moreover, there are some useful “side effects” to MISRA compliance. For one, compliant code is also easier to verify. That means both Static Analysis and Dynamic Tests will benefit from it, and in particular, Formal Methods run much faster. This is because the MISRA guidelines avoid complex constructs like dynamic memory allocation and pointers to pointers.

But perhaps the biggest “side effect”: You get more safety. Guidelines are there for a reason. And while they can be annoying, they will prevent bugs if you do it right. Naturally, this requires effort.

Lastly, nothing is perfect. If you feel a coding guideline does not get close to the right bugs, then why not contribute to its working group or committee?