Coding guidelines are always useful. If you feel differently, you are doing it wrong. In this article, I show how to significantly reduce the developer burden and make the guidelines work for you, instead of you working for them. We cover different types of guidelines, common setup problems in Static Analysis tools, and explain how to take shortcuts that won’t hurt compliance.

In my experience, many people misunderstand coding guidelines, even some professional developers. Let’s clear up some misconceptions and learn how to make them useful, instead of a pain. In this article, I use the popular MISRA C guidelines as a specific example. Embedded software developers use them commonly, and I know them well from my own experience.

This is part 1 of 2…

Why should I use Coding Guidelines?

Every programming language has its pitfalls and complexities. And as we discussed before, humans are very good at tapping into them. (And GenAI, too, just in case you think there is a loophole.) Coding guidelines, sometimes also called coding standards or coding conventions, help us avoid errors by providing “formalized experience”. In practice, they are nothing more than a catalog of “bad patterns”. Some cause bugs, others maintenance problems, and some verification challenges.

Coding guidelines make sense for everyone. For junior developers, they are a form of education. Over time, they will know what to avoid and write better code. For senior developers, they are confirmation they have not forgotten anything. For businesses that develop software, they are a form of risk management. And for safety-critical applications like airplanes, cars, and medical devices, they are practically non-negotiable, and highly recommended in safety standards like ISO26262.

Don’t follow them blindly

Good guidelines should also come with a rationale, so that we can truly understand them, and decide if:

- Does this guideline help achieve my goal?

- Does it have any real impact?

For example, there is a coding guideline for Python that recommends wrapping long multi-line statements with parentheses instead of backslashes. At first glance, it sounds like nitpicking. However, the rationale is that backslashes can change meaning if whitespace changes, potentially causing runtime syntax errors.

Knowing the rationale, we may even like the rule and apply it voluntarily. However, if we have some other means to detect syntax errors, or even to avoid whitespace errors (hello, IDE!), then we may as well decide that this rule gives us no benefit.

Understanding the rationale of each guideline allows us to make smart choices.

Static Analysis is perfect for Coding Guidelines – or is it?

The best way to check coding guidelines is this: Show your code to a colleague and ask whether he/she can spot any bad patterns. This is the preferred way to annoy your colleagues and miss bugs.

Joking aside. Of course, the only sensible way to check coding guidelines is to use Static Code Analysis. It can automatically and tirelessly find bad patterns, and dig deeper to evaluate also “non-patterny” properties like the rule “you shall not access NULL pointers”.

If you are thinking right now that GenAI could also be a good way to check coding guidelines, have a look at this article to understand why that is not a good idea.

A sea of warnings

Let’s say you are on my side and you have installed your favorite static analysis tool (bonus points if you have an IDE integration!). You also enabled the right guidelines and obtained your first results. Now the “fun” begins:

- You get too many warnings. Starting to fix them seems hopeless. Hence, you’d rather uninstall the tool and forget everything you saw.

- You see a lot of False Positives. Your tool reports issues that are certainly none. This makes it impossible to see the real issues – a needle in a haystack.

- Some specific rules make no sense on your software. For example, the guideline says that your variable names are too long, but you have limited control since the code is automatically generated, or some APIs are just defined that way.

- You feel that some rules don’t bring you any benefits for safety or performance, but somebody forces you to apply the rules.

- There is a way to deviate from the rules, but that means going through a heavy process that will consume even more time.

If you are working on commercial embedded software, coding guidelines can become a frustrating nightmare. You make no progress anymore. You suddenly find yourself wading through thousands of useless warnings, pulling all-nighters to suppress similar warnings again and again robotically… All in the name of “compliance”, with no real benefit. This is the stuff to make developers hate their job.

Finally, you open your favorite social media platform and complain that coding guidelines are a waste of time.

Blind use of coding guidelines can make developers unhappy very fast.

Let’s fix this.

Background: The MISRA Guidelines

Many coding guidelines already exist. For example, the CERT standard (focus on security), or the PEP8 guidelines for Python (focus on style). Certainly, you can also create your own, but that is typically not a good idea. If I sold software to you with the assurance that I used the “Martin Coding Standard”, would that put your mind at ease? Clearly, guidelines can be anything from well-made to a catastrophe that contradicts itself. And both types exist (I won’t drop names, no).

For the rest of this article, we will look at the MISRA guidelines. They are a proven and mature coding standard for embedded software, focusing on safety. Arguing that they make no sense would be challenging, given their almost 30-year track record. They are aiming at making C and C++ safer by avoiding undefined behavior and also reduce verification challenges.

The 2023 edition of MISRA C has 200 rules, grouping them into three categories:

- Mandatory rules (23x): These rules must be followed without deviations.

- These are rules that prevent errors of high risk, for which no valid technical excuse exists.

- E.g., don’t read uninitialized values (rule 9.1), don’t declare functions implicitly (17.3), ….

- Required rules (137x): You can deviate from these rules with a good excuse (more on that later).

- e.g., release all dynamically allocated resources (rule 22.1), do not use memory allocation functions (21.3), and external identifiers must be unique (5.1).

- Advisory rules (40x): They can be seen as recommendations. Fix to a reasonable, practical degree.

- E.g., a project should not contain unused type declarations (rule 2.3), pointers should not be stored in integers (11.4), and goto should not be used (15.1).

Note: We omit the MISRA Directives here. These are additional guidelines that Static Analysis cannot fully check automatically.

No guidelines without a compliance process

Imagine that you run the guideline checks, but you suppress all the warnings, or you never look at them. That would be no good. Therefore, the MISRA guidelines also define what you need to do to be compliant, while fairly keeping in mind that it is not always possible to follow each rule.

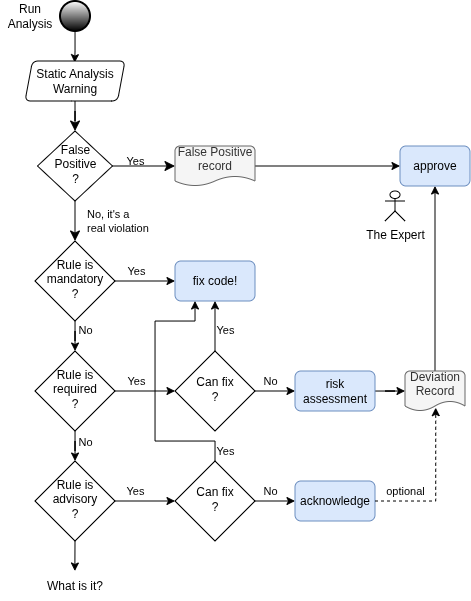

Here is a flowchart that describes the process, depending on the category of warning that you get:

False Positives: As we know from earlier articles, Static Analysis tools can always throw false warnings; that’s just their nature. Thus, we can suppress False Positives regardless of category, but of course not without proper documentation. An investigation record must be kept and approved by an appropriately qualified technical authority (tool vendor, QA team, …).

Mandatory Rules: You must fix your code. No way around. Do you expect me to say anything more?

Required Rules: If you want to deviate from them, you need a formal Deviation Record, which captures the code location, the circumstances, a risk assessment, a justification, and requires approval by someone who has expertise (The Expert).

- Deviations must be treated one by one, not in a “justify all” manner.

- Static Analysis tools often allow for suppressing a warning with a user comment in the code. Sometimes the comment is some kind of alphanumeric identifier of the deviation record, which is stored in a separate database.

Advisory Rules: Deviations do not require a formal process. The important thing is to acknowledge them somehow, to make it clear they have been accepted intentionally, and not ignored or accidentally missed.

- One way to acknowledge is to again use your Static Analysis tool’s suppress in code functionality. In this case, an informal comment might be enough.

- At least acknowledge their existence (with location and type) in a final code analysis report.

😈 Lastly, convenience is never a valid justification! You cannot skip guidelines simply because you feel it is too much work. That would defy the whole purpose of guidelines. Good justifications are about quality (e.g., run-time behavior and resource consumption), necessary hardware access, or third-party code that cannot be changed without risk.

Deviations from the guidelines are costly but sometimes necessary. Some require a formal process to capture the risk and justification.

What’s actually the time-consuming part?

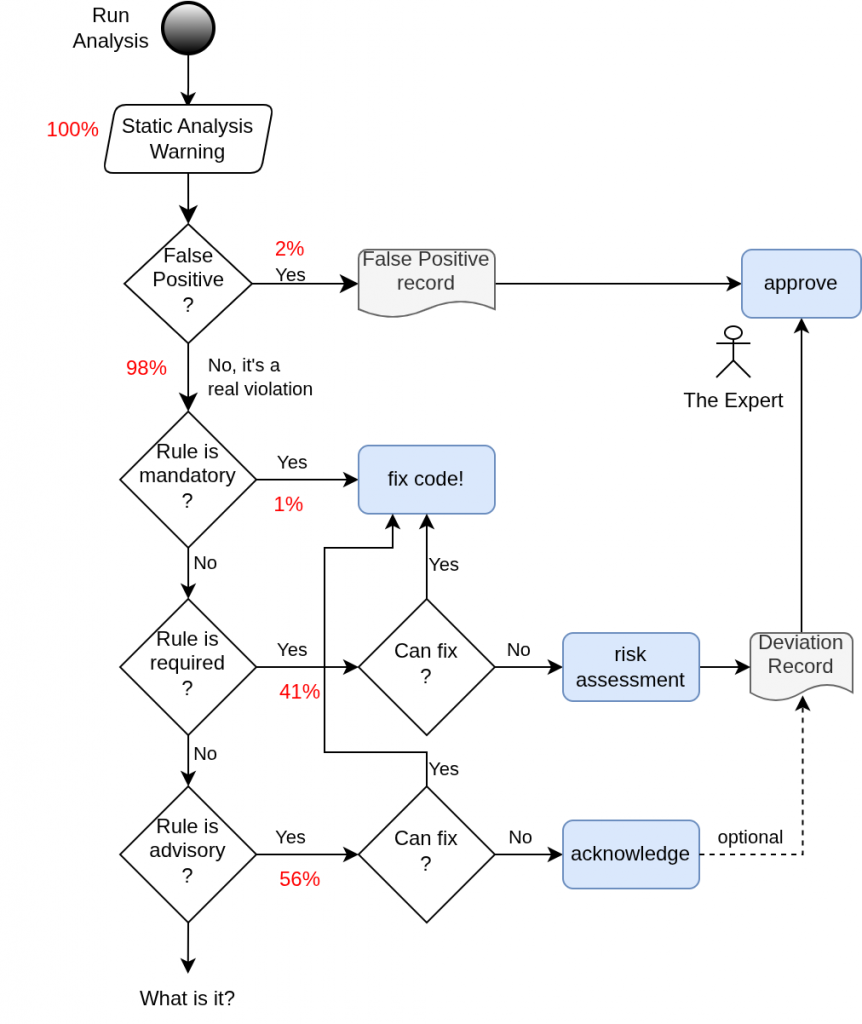

Let’s throw in some numbers to understand the main factors that make coding guidelines slow and tedious. We want to quantify our pain and find the real bottleneck in our process.

Rules that take the most time

First, let me add some typical numbers to the flow chart, showing how often the different rule types are violated on a typical industrial code sample (in my experience, I have no way to prove this). These numbers are pretty robust across industry and code maturity. Yes, there is some variance, but…

Typically, most warnings are violations of advisory rules. However, they are not our biggest problem. Since they are “best effort” and there is no formal process required, there are easy ways to handle them efficiently. More on that later.

The second largest group is violations of required rules (~40%). And this is our main problem. They appear frequently, and they either must be fixed or justified one by one through a formal deviation process (that involves multiple people, including The Expert, who might be busy). This will take a LOT of time and paper. Moreover, after code changes, we have some extra work for all our deviation records: First, we should check whether the assumptions and risk evaluation are still correct. Second, we must update the precise code locations in the deviation records. I reckon that probably 80% of the review time is spent on deviations from the required rules. Feedback welcome.

Everything else has barely any room to improve. Relatively speaking, False Positives are rare, especially with a good Static Analysis tool. And finally, violations of mandatory rules are typically below 1% and not worth discussing. No magic for them – just fix it.

This quick analysis tells us one thing:

To save the most effort, focus on minimizing deviations from required rules.

A frustrating calculation

How bad is it? Let’s say you are maintaining a project with 50 thousand lines of code, and you are trying to be MISRA compliant. According to the numbers above and a typical defect rate of 50 per 1,000 lines of code, you would have around 2500 guideline violations coming from your static analysis tool, and around 1,000 of them would be required rules.

Sigh…1,000 issues that need to be either fixed or undergo a formal deviation process. Even if we are optimistic and assume that it only takes one minute per warning, then that would be 17 hours of boring, tedious work.

What’s next?

This article covered the basics and ended by identifying the typical bottleneck. Next time, we address how to remove it.